Cheng Xuan Li

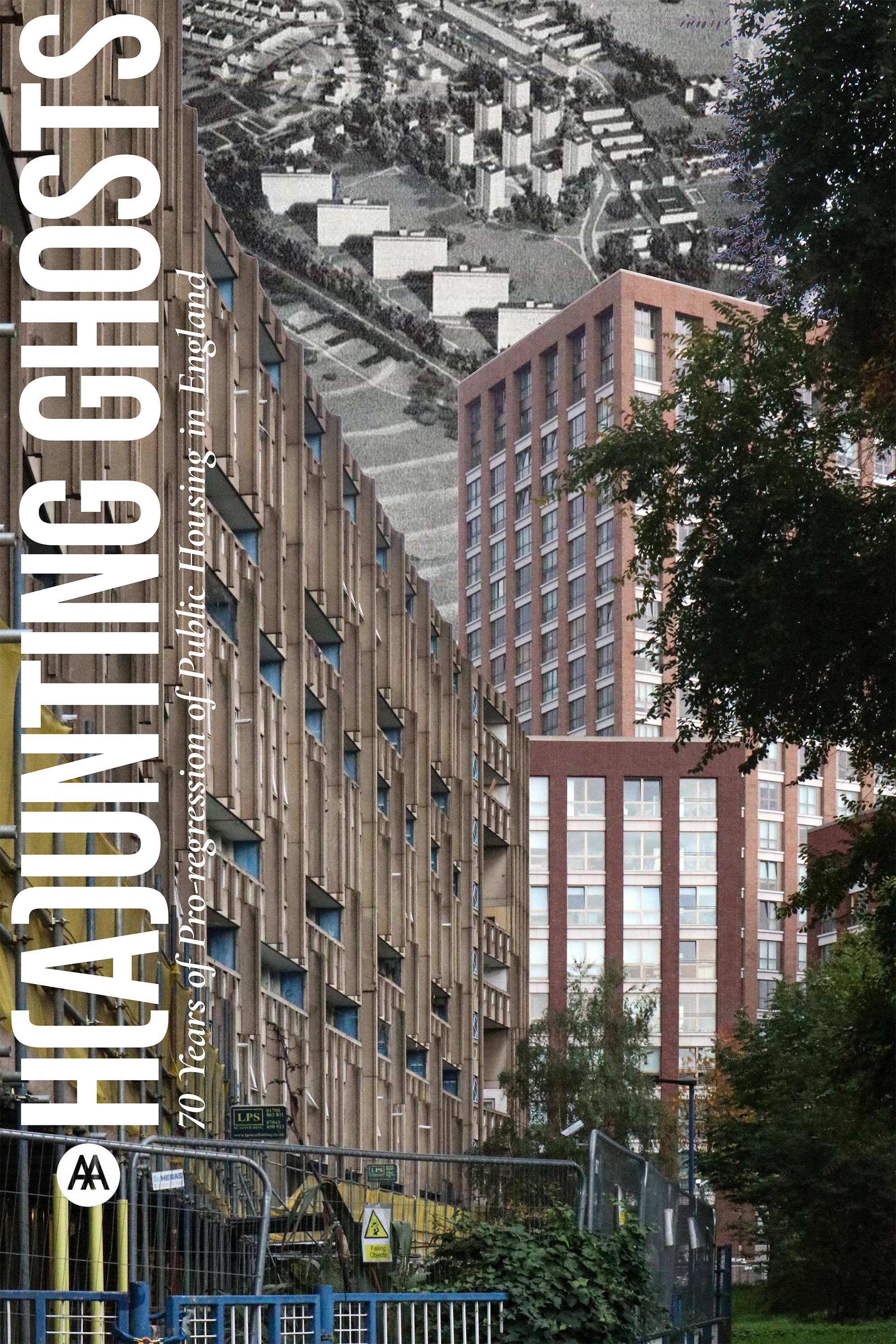

H(a)unting Ghosts, or the grand rethinking of the 70 years of pro-regression of public housing in London

Keywords: #Material History #Public Housing #Criticism

Year: 2022

With William Hutchins Orr

Part of the AA Diploma History and Theory Studies Thesis

Exposé: The Necromancer and the Exorciser

“Neave [Brown], it has taken my practice [Karakusevic Carson Architects] 15 years to build just over 200 homes, whereas in seven years in Camden you managed something close to 700. What were the special conditions to make that possible?”1

What one is faced here, is the dramatic and drastic tension between the continuity or inheritance of the discipline of architecture, and the inside-out rearrangement of the state of affairs in their entirety and the unprecedented overturn of political economy that serve as the material substrates for the housing projects of Brown and Karakusevic. Brown is a (though former) public-sector architect, architect of various highly publicised British council housing estates, modernist housing specialist. Karakusevic is Brown’s student, a private-sector architect, running a practice dedicated to contemporary public housing projects with public-private joint venture. If one is to refer Brown as the weaver of the Municipal Dream2 of public housing and the necromancer of béton brut, then Karakuse-vic should ironically be the one to help to undermine if not to knock down the short-lived remnants of the oft-criticised welfare state and the exorciser of its utopia.

Arguably, the multiplicity of their relations is reflective of a shift in the disciplinary knowledge and material interest of architecture. If the work of the architect as the necromancer of material objects should be put into the historical dustbin of wasteful and exhaustive realm of “styles,” just as how modernism had treated its previous epochs of “styles,” then by 1980, modernism itself should have already been thought by many to belong to the same dustbin of wayside materials, with its unique hallucinations of the architectural utopia “reduced to historical curiosities if not Faustian nightmares.”3 In similar sense, if the role of the architect up until the official death sentence of modern architecture depicted by the famous image of the fall of Pruitt-Igoe by Charles Jencks4 that risked as much over-simplification as the communicability it gained, then the architect should have officially been empowered to take up the refreshingly new enterprise of “post-modernism” since La Strada Novissima5 from where one discerns merely pseudo-events, partial-revivals and a cacophony of ad-hoc bricolage or eclectic pastiche.

It is therefore argued that in line with all such paradigmatic shifts (the internal contra-dictions in periodisation and accountability of which, though, remain partially subject to criticism and are therefore not unchallenged), speculative6 and idealistic architectural discipline also features a by no means insignificant historical change from the role of the necromancy of material processes and weaver of utopian ideals to that of the disenchantment of its so-claimed hallucinations of the former, and the subsequent displacement of all previous dream-makings as some sort of historical waste – if one could risk vulgarisation, it is the change from the architect as necromancer to exorciser, indeed. The necromancer brings about the seductive phantasies of the stone-made Fedora of assumptions and phantasy,7 only to render physical in concrete the utopian ideals. Public housing could be the emblematic example of the failed utopia par excellence where the exorciser renders visible all the violent contradictions of public housing utopias to liquidate them eternally. “Architecture or Revolution,”8 as necromancers have claimed, are now too pale and futile to provoke any radical historical change: we are now left with an exorcised world, a stásis devoid of any possibilities for change, disillusion of an autonomous Architecture, and the impossibility of a Revolution.

It is not merely on the will of their own that the exorciser who deterred almost all the public housing projects not in the possibility of conceiving them as utopian images but also in the ability of financially and politically support such projects. Yet inevitably, during the recent decades Britain witnessed a drastic decline in the profession and an arguable regression of the discipline, and projects of anticipation and conceptualisation by the profession in as recent as a decade, seem not to have vanished off in their entirety but have remained and have transfigured to be transfixed in the traces of material frustration and exhaustion, dereliction and vandalism, devised stigmatisation and acquiesced depression of the concrete utopia: these characteristics are not only descriptive of a spatial condition but a societal symptom that prevailed in the still-standing housing estates in their undeath. Social symptoms should never be expected to emerge and disappear without a firm causality with their material substrate, and knowledge of material basis should foremostly be attained through the analysis of the superstructural representations. Shockingly enough, during such dialectic reasoning, after almost four decades of experimental disenchantment, the exorciser is found to be faced with the return of ghost of the necromancer again.

-

Paul Karakusevic, in Project Interrupted, Lectures by British Housing Architects, pp. 12-47. Neave Brown was (formerly) a council architect working for London Borough of Camden architecture depart-ment. Brown is the chief architect for Alexandra Road Estate, now a Grade II* listed building. Paul Karakusevic is a student of Neave Brown and is running the practice Karakusevic Carson Architects in London, working on public housing projects and large-scale civic projects in the United Kingdom. This quote is an extract from a conversation between Brown and Karakusevic at the Barbican centre on 23 July 2015.

-

Taken from John Boughton, Municipal Dreams, the Rise and Fall of Council Housing.

-

See Reinhold Martin, Utopia’s Ghost, Architecture and Post-modernism Again, p. 152. See also Reinhold Martin, “Utopia's Ghost: Postmodernism Reconsidered.”

-

Charles Jencks, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, p. 9. In the architectural discourse that Jencks gave to the end of modern architecture, it is at the exact date and time of 3:32 PM, 15 July 1972, the destruction of Pruitt-Igoe Housing Complex in St Louis that marks the death of modern architecture.

-

It refers to the travelling exhibition at the 1980 Venice Biennale. See Martin, Utopia’s Ghost, pp. 152-54.

-

This is to be distinguished from some of the contemporary usages of the term, for example, in terms as “speculative market” that refers to the potential or provision of the profitability and increase in exchange value of a certain real estate property. Here this term is introduced to refer to the qualities of things or of relations being idealistic, evocative, visionary, anticipatory, unfinished, premature and “utopian.”

-

See Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, p. 32.

-

Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture, p. 269.